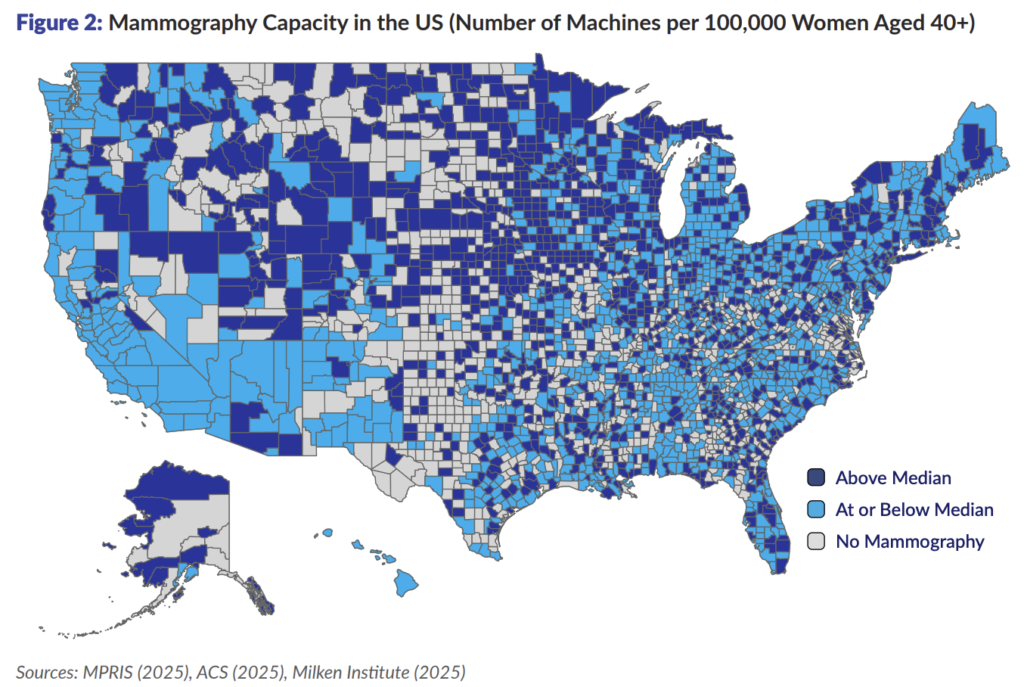

A new report from the Milken Institute has quantified the geographic disparities in mammography access across the United States, estimating that approximately 9,600 additional breast cancer cases could be detected earlier if low-capacity counties performed at the same level as high-capacity areas.

The report, “Opportunities for Local Mammography Deployment,” analyzed the location of every certified mammography machine in the United States using data from the FDA’s Mammography Program Reporting and Information System. The analysis identified 890 counties with no mammography machines and significant capacity gaps across much of the Southwest and Great Plains regions.

The study found that counties with lower detection rates tend to have smaller populations, higher percentages of racial and ethnic minority populations, higher poverty rates, lower health insurance coverage, and higher proportions of limited-English-speaking households. The report also found that only 38% of female Medicare enrollees in low-capacity, low-detection counties had received a mammogram in the past year, compared to 48% in high-capacity, high-detection counties.

“While some locations have a high density of mammography resources and a corresponding high rate of breast cancer screening and detection, other places have far fewer resources and a corresponding low rate of screening and detection,” the report states.

The analysis projected that if low-capacity and no-capacity counties could achieve detection rates comparable to high-capacity counties, approximately 4,200 cases could be caught as ductal carcinoma in situ before progressing to later stages.

The report identified 74 counties that would yield high return on investment for both overall breast cancer detection and early-stage DCIS detection with additional mammography machine deployment. These counties include areas such as Broward County, Florida, and Adams County, Colorado.

However, the report emphasizes that additional machines are necessary but may not be sufficient to close detection gaps. Other barriers including cost, language access, inability to take time off work, and lack of engagement with the healthcare system must also be addressed.

Counties with high mammography capacity but low detection rates suggest that factors beyond machine availability constrain screening access. The report notes that even small copayments are associated with lower adherence to screening guidelines, and lack of a regular healthcare provider is associated with lower mammography use.

The Southwest represents a particular area of concern, with a large cluster of counties showing both low capacity and low detection rates. California, despite having a high number of total machines, has lower per-capita capacity due to its large coastal population.

The report used county-level breast cancer data from 2017-2021 and female population data for women aged 40 and above, the age range for which mammography screening is most commonly recommended.

More than 42,000 women die annually from breast cancer in the United States. The breast cancer mortality rate fell 44% between 1989 and 2022, with increased screening contributing to approximately 25% of that reduction.

The Milken Institute report was authored by Andrew Friedson, Abigail Humphreys, Bumyang Kim, and Katherine Sacks and released earlier this month.